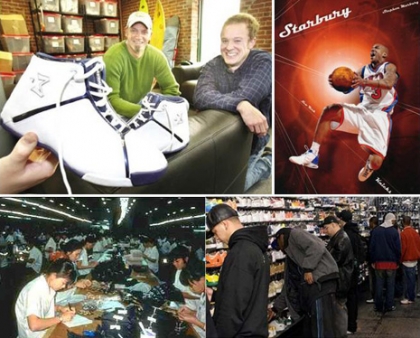

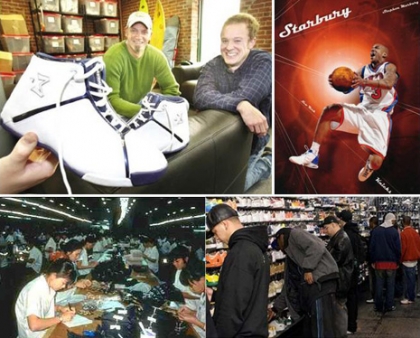

T.J. Gray, left, and Ashley Brown, principals of Rocket Fish, an industrial design company in Portsmouth, designed the Starbury sneakers, which retail for $14.98. The affordable basketball shoe is endorsed by New York Knicks guard Stephon Marbury.

If you shoot hoops you're probably aware of the Starbury line of shoes, endorsed by basketball star Stephon Marbury. The owners, Steve & Barry’s LLC, market the line as inexpensive, high-performance basketball shoes.

You may have also read about the controversy surrounding exactly how “sustainable” these shoes are.

Starbury shoes target an underserved market segment: inner-city kids. Their product addresses the social injustice of young underprivileged street players not being able to afford top-performing athletic shoes.

Starbury sports a simple message: "Its about the kids." The company provides affordable footwear, which allows youth to enjoy sports without having to shell out for a pair of Air Jordans.

Most reviews of the Starbury line have been positive, contrasting Starbury with Nike, singled out as the black-hatted villain for its high margins on traditional retail sales.

Starbury also states their fiscal goal are agressive. Their strategy pivots around omitting the significant costs of extravagant marketing, enabling a retail price of just $14.98 a pair when launched, and now, some 18 months later, just $8.98.

But I’m wondering, are we thinking about all the kids involved? Certainly, an article in The Nation quotes experts who doubt that the shoes are entirely free of exploitative labor. Their doubts are expressed in subjective terms; I thought I’d turn to the numbers for some clues.

My approach: to explore this from a comparative-product, systems point of view, taking into account the social aspect of design and sourcing as opposed to less objective, purely marketing approaches. Too often, words like 'sustainability' provide a fuzzy, gentrified view of the environment and ignore the people they are affecting.

Companies can determine their cost-to-profit ratio using a basic multiplier formula: the raw cost of materials times a standard industry multiplier gives them enough to pay for design, manufacturing, shipping, and marketing…and make a decent profit.

To illustrate the Starbury marketing case, let’s compare them to a conservative look at Nike's Freight On Board (FOB) using a multiplier of 8 to back out its cost on a traditional retail price:

$125 MSRP divided by multiplier of 8 = $15.63 FOB per pair of shoes.

So Nike charges $125 for a pair of shoes that cost $15.63 to produce. Let’s now give Starbury the benefit of the doubt for thin internal margins and cut that multiplier in half:

$15 MSRP divided by multiplier of 4 = $3.75 FOB.

A multiplier of 4 is the slim manufacturing margin in the footwear category, even when working at large volume.

Of course, these are estimates, but likely close to what we might expect resulting from their respective products. If we assume similar materials, technologies, and volume breaks, the production factory was significantly squeezed to pull this off. A 2x difference could be acceptable in these FOBs, but a 4x+ gap seems logically problematic.

So, which kids is Starbury helping?

Likely not those in Eastern Asia, where the shoes are manufactured. From a global view, is this 'socially just' product a net positive? What other design and material externalities might be present to manufacture these?

My point is to highlight the need for critical systems and environmental thinking in league with social responsibility, not just marketing hype. To paraphrase Jack Kerouac, “Words, words, the stars are words. Give me the numbers.”

Such an analysis may show that an improvement for inner-city kids in the US actually decreases the world’s social outcomes.

Marketing departments don’t typically get involved in such abstract analysis. But it’s something that R&D should absolutely bring into their own analytical thinking.

Images: Loozekannon @ Photobucket; John Lei for the NYTimes; Rich Beauchesne