Let me share with you a small experiment I did during my travels in India.

Like all architects and designers I share a common curiosity about the innards of products, which often leads me to dissecting and disassembling them. I recently found sketches I had made of houses and their sections while visiting parts of India characterized by extreme climates. I revisited those sketches, this time looking through a lens of sustainability and environmental sensitivity.

The sections are not only telling of the local construction and vernacular but also how practices that have evolved over centuries can teach us about adapting to climates more sustainably today.

While there are many lessons to be learned from vernacular architecture in these areas, it is noticeable that most aspects of sustainability are absent from modern buildings in these regions. This is due to many reasons: rapid development, use of foreign materials, design methods, and construction systems.

LadakhClimate:

Ladakh is a semi-autonomous region in the North-Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. Lying in the rain shadow of the Himalayas, this high altitude desert is characterized by a rugged landscape of mountain ranges rising up to 6500m. Ladakh is governed by its harsh climatic conditions with short summers scorching the land with temperatures of up to 40° C (104°F) while its long winters can be bitterly cold with temperatures falling as low as -40° C (-40°F).

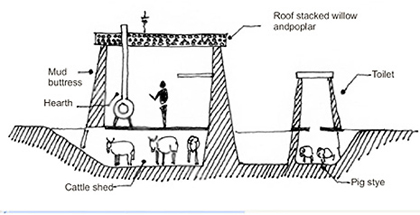

1.

Response:

A village mainly consists of several buildings in close proximity, either sharing walls or separated by narrow paths The effect is that of a maze. In the village the buildings are all made of mud bricks sealed by smooth mud cement. The walls are thick and the mud is mixed with hay to provide insulation. The roof is covered with a 2-3 ft layer of fodder and poplar branches. This not only helps to insulate but also serves as a storage space for the winter months. The living quarters typically consist of 2-3 rooms, of which one is a kitchen -- most daily activities revolve around the main hearth. This provides heat in the winter months and is fueled by the waste of the cattle. The cattle are kept in an additional below-ground level. Through induction the heat generated by the cattle helps warm the upper level. The dry pit toilet is built out to the side of the main living space over the pig sty. The sty’s entry door has a small hole for air intake. The sty is cool and dark, creating a low pressure zone under the toilet pit which draws fresh air from the door opening and ventilates it out through an air shaft thus keeping the area free of odors, flies and insects. The excrement from the toilet and pig waste is collected and used as manure in the fields. “Waste” is a modern phenomenon. The notion of waste is non existent in traditional cultures like this one in Ladakh.

BhujClimate:

Being in the arid part of the country, the climate of the Kutch region is extreme- hot and dry during summer and very cold during winter. Summer is rather severe in the entire state of Gujarat with poor rainfall if any. This area also experiences significant seismic activity.

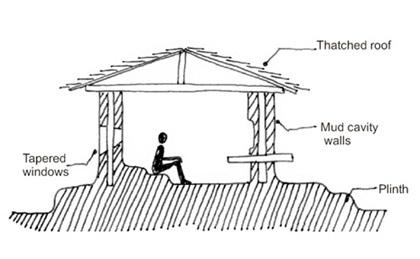

Response:

Homes are built around a common open space. As families grow, additional homes are added around this central space. Often there are no windows or one at most. Wet black mud available from nearby creeks is used to simplify and speed construction. The walls, which are 60 cm (2 feet) thick, are made of mud and chaff and incorporate a space to improve insulation. Windows are inserted in opposite directions, one directed to the wind and the other near the stove. Also there is one door, a kitchen cabinet and cantilevered shelves. The roof is built by tying an inner and outer spiral of young palm branches around sturdier branches, topping the structure with grasses for layered insulation. The roofing materials are water-resistant but allow for hot air within the structure to escape, which further helps to regulate the interior temperature. The entire structure is made of lightweight materials which provide both insulation against the desert winds as well as flexibility during earthquakes.

KeralaClimate:

Kerala has a tropical climate and remains pleasant for most of the year. Unlike most other parts of India Kerala’s climate does not include a dry season. The temperature peaks at a relatively moderate 33°C (91°F). The southwest monsoon contributes to high humidity and rainfall can easily last for days at a time.

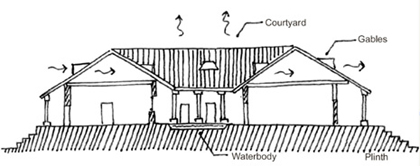

3.

Response:

Classical Kerala architecture incorporates a bamboo frame topped with thatch or shingled terracotta tiles. Structurally the roof is supported by the pillars on walls resting on a plinth which is raised from the ground. This affords protection against dampness and insects in the tropical climate. Gable windows at the two ends of the home provide attic ventilation. This creates a ventilated, sandwiched space between the ceiling and the roof, which conducts heat away from the ceiling and in turn from the inside of the home. The flooring is made out of Indian patent stone, which is usually colored black to keep the interior space dark and cool. The home itself is built around a central open-to-sky courtyard space, which provides ventilation and light. The courtyard in a traditional Kerala home commonly features a shallow pool of water, which helps to cool the home by continuous evaporation under the hot skies. The differential heating of spaces creates ventilation inside the house by pulling cool air into the home. Most daily activities occur around this courtyard. The roofline projects out to shade the walls from rain and sun and also creates large shadows preventing direct sunlight on the home’s walls.

Recovering indigenous culture must go beyond reclaiming artifacts from western museums or maintaining an objective, academic distance. We may be better served by recognizing and adapting often-sustainable traditional values by incorporating them into our contemporary built forms.

Sources:

All Illustrations: Rajat Shail

Photo 1 Image Credit: Falk

Photo 2 Image Credit: Rajesh Kakkanatt